Memories of Eldridge

Messages of sympathy and memories of Eldridge may be sent to

memories-of-eldridge@ucdavis.edu.

If you wish to have your message included on this web page, please let us know.

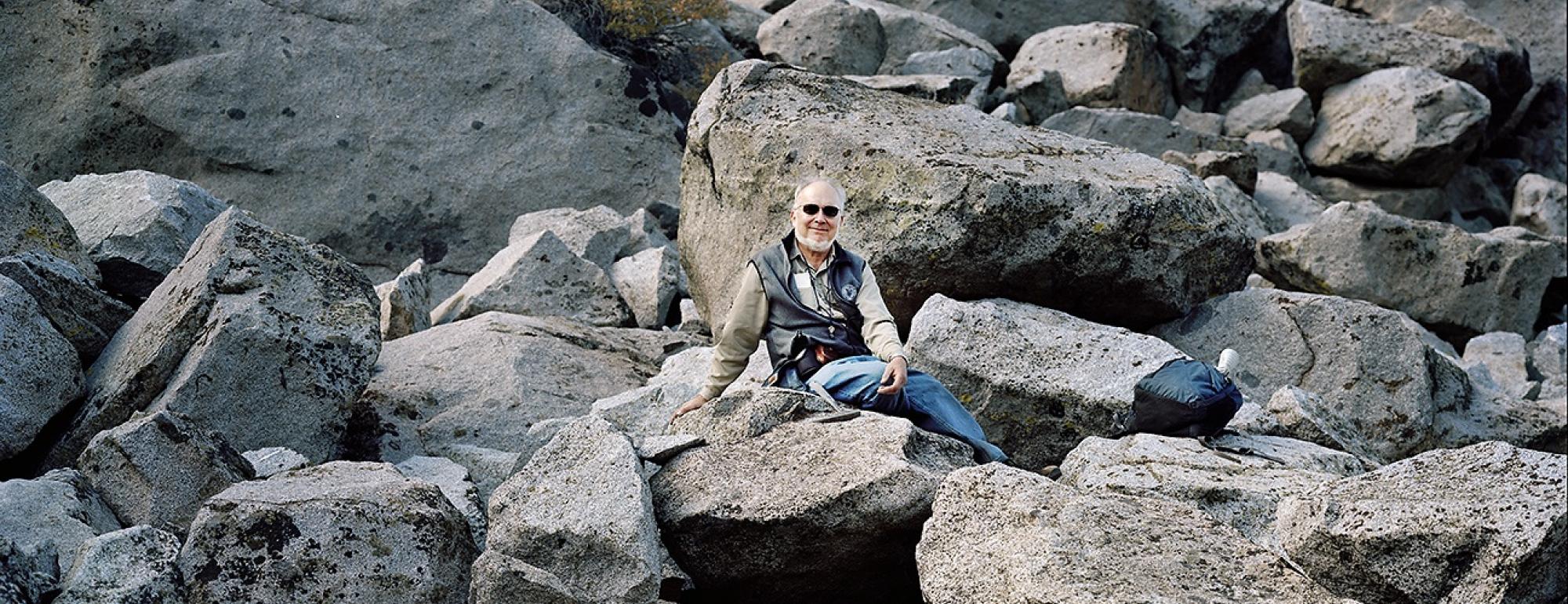

photo: "Eldridge on the Rocks." ©Christopher Woodcock.

Eldridge Moores (1938-2018)

Instruments in clean rooms, underneath the ground

Measurements and data, computers all around

That’s not where you would find him, he’d really rather roam

His lab was in the mountains, far away from home

O sing a song of Eldridge, in melody and rhyme

The last great field geologist, exploring back in time

Vourinos and Troodos, rocks on every hand

The bottom of the ocean, cast up upon the land

The growth of understanding — the forest, not the trees

By studying the mountains, he understood the seas

Nevada and Antarctica — the rocks they looked the same!

And as he saw them in the field, a great idea came

A mighty supercontinent, he saw through time and space

And in his mind, Rodinia’s ancient map fell into place

Always seeking answers to historical unknowns

Consulting Nature’s archives, written in the stones

His field quest is left to us, we need to carry on

A scientific hero, sadly, now is gone

O sing a song of Eldridge, in melody and rhyme

The last great field geologist, exploring back in time

I somehow missed the news of Eldridge's passing until now. Aside from his brilliance as a scientist he contributed greatly to the Nature and Culture program which lived as a vibrant fire between the arts and sciences for over a decade. Eldridge was a devoted researcher, outstanding teacher and somehow a mischievous presence whenever I saw him.

I am glad to have known him even a little.

Daniel Cox, UC Davis Physics

I am a reporter with the Los Angeles Times. Over the last 20 years, Eldridge and I spoke over the phone whenever I had a story that touched upon the geology of California. He was always generous with his time, eager to talk about gold in the Sierra foothills or the rain beetle (pleocoma) and its debt to plate tectonics. He was adept in explaining science in terms that a general newspaper reader could understand, and he made my job easier. A good journalist should always keep someone like Eldridge on speed-dial, but he was one-of-a-kind. I always wanted to join him on a field trip out and around the Sacramento Valley, and I regret that never took place.

I am so very sorry for his passing, and I hope my sincere condolences can be passed along to his wife and family.

Thomas Curwen, Los Angeles Times

"Eldridge Moores: He Looked at a Jumble of Rocks and Saw the Sierra Being Born" by Craig Miller, KQED Science

This contribution is late, for it started and stopped frequently. I could not find the works to convey my sadness and sense of loss with Eldridge’s passing. I finally had to give up, and submit this in its inadequate form.

I first interacted with Eldridge Moores indirectly, when I was an undergraduate Physics major. I traveled to and attended a two-day short course in Bakersfield. The course was on the relatively new field of plate tectonics and was sponsored by the San Joaquin Geological Society. The five instructors included a who’s-who of California geologists specializing in plate tectonics. Of course, one of those young stars was Eldridge Moores, a geologist from the Department of Geology at UC Davis. The 15 hours of lecture in those two days were eye openers into the relatively new subfield of plate tectonics. In one of his talks Eldridge provided the audience with an introduction to the concept of ophiolites complexes as pieces of ocean crust that were thrust up and exposed on land. At that time I did not know that the nature of the ocean crust (and ophiolites) would occupy much of my career. I still have the notes from that amazing course.

I did not directly meet Eldridge until 7 years later, at a meeting on the island of Cyprus, the home of one of the most famous ophiolite complexes in the world, and one where his work had made him famous. Eldridge was on sabbatical leave, and I was in the process of moving to UCD. The visit included my first field trip with Eldridge. I would later go on to other trips with him, in Cyprus, central Nevada, the Coast Ranges, and his beloved Smartville Complex. My last trip with him was last March, when several of us went to the Oroville Dam site. Always, Eldridge was such a wealth of information and, more importantly, of ideas. I did not always agree with his scientific ideas, but I never stopped learning from him. We are all going to miss those wonderful opportunities.

We also will miss Eldridge’s participation in our Department seminars on Wednesday afternoon. When the seminar was over, Eldridge would raise his hand to ask a question. He always started by kindly complimenting the speaker on her/his presentation, and then move into a particularly cogent question. Some of us noticed that the questions were always relevant, even when Eldridge appeared to have been asleep during part of the presentation.

After he retired, Eldridge would stop by my office to talk a little science, and tell me about his kids and grandkids, of which he was justifiably proud. I am so going to miss those conversations, perhaps most of all.

Thanks Eldridge for these many years of conversation, field trips and friendship.

Jim McClain

Professor, The Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

UC Davis

"Cool Davis says goodbye to a good friend, Eldridge Moores" by Lynne Nittler

We were deeply saddened to hear of Professor Moores's passing. It was a shock to all of us.

Professor Moores was a great person who touched many lives, including ours.

He was blessed with so many wonderful experiences and a long and productive life.

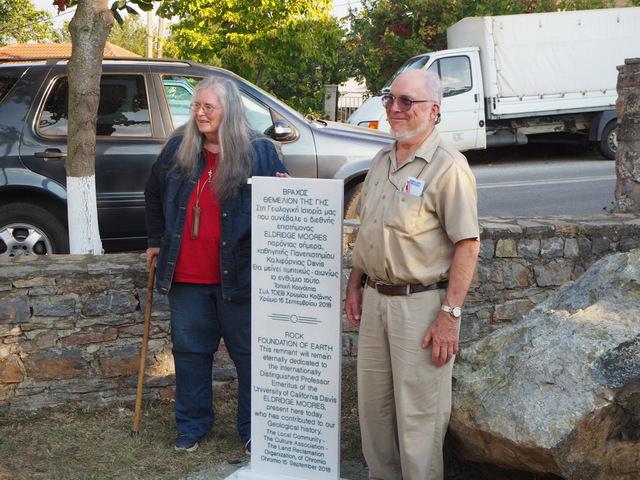

We will always treasure our time spent with him and all of you at Chromion, Greece in September 2018.

In Sympathy,

Ioannis and Lola Papaioannou.

The Culture Club of Chromion.

The Community of Chromion.

I had the luck to be with this charming, wise, generous scientist–poet several times over the years. I admired his depth and precision, his visualization of the complex life of matter around us – he was at home in the mind of the underworld as well as overworld. He made things clear. What a gift his life has been.

Gary Snyder

Read at the ceremony in Celebration of Eldridge’s Life

- Robert J. Twiss

Helen and I were both devastated by the terrible news of Eldridge’s death, as I expect all of you were. But in our grief, we have tried to focus on the joyful memories of Eldridge that have filled the past 47 years of our friendship.

To me, he was an ever-present companion of the workday. Our offices were always adjacent, and on a daily basis, we shared teas, lunches, professional and casual conversations, often with much laughter; and we shared the ups and downs of personal and professional life, as well as political goings-on and world affairs. We saw eye-to-eye on almost everything. Even writing our two textbooks, while a trial for both of us at times, never threatened the strength of our friendship. I never ceased to marvel at his encyclopedic mind, and his ability to think out-of-the-box and to synthesize, in truly original ways, the vast store of detailed geologic knowledge that he could call up from his memory. His creativity and clarity of thought often pointed the field of tectonics in new and stimulating directions. Beyond that, he was able to encompass and contribute to endeavors well beyond his geological specialty — truly a Renaissance man.

In a very personal way, however, it was our frequent get-togethers that made life in general, and geology in particular, so much more fun and stimulating. He enriched my life and my career, and I am ever indebted to him for his presence and support year-in and year-out, and for his steadfast friendship.

Postscript added later to memories of Eldridge

Walter Alvarez mentioned, in his memories of Eldridge at the ‘Celebration of Eldridge’s Life’, a certain bachelor party, which was held one evening in the Graduate College at Princeton University after both he and Eldridge had become engaged to be married at about the same time, and Walt specifically mentioned the code of Omertà (the oath of silence) that governed their recollections of that party. I was a beginning graduate student at Princeton at that time, and if that was the party I am thinking of, I was there, and I never committed myself to Omertà ;-)))

The only thing I remember about that party is that at one point during the festivities, Eldridge and Walt agreed to a beer-chugging contest between them — a race to see who was fastest at downing a full glass of beer. At the signal to start, Walt began to gulp at his glass of beer… gulp… gulp… gulp… gulp at fast as he could. In the meantime, Eldridge somehow simply opened his gullet and poured the beer down into his stomach — no gulping, just a straight pour like down the kitchen sink. It was gone in no time, while Walt was still gamely gulping away. And Eldridge claimed his victory with a triumphal flourish of his empty beer glass high into the air, and a broad grin on his face!

And in case you might be wondering, Judy, I never saw him do that again!

For Eldridge Moores

The rocks, they called to him.

From far beneath the oceans

to mountain peaks in the thinnest of atmosphere,

the rocks called to him.

He grasped the foundations of the planet,

comprehended the current of the eons,

deciphered the whispers of the echoes

of the subsonic language of the tectonic plates.

With his arms and hands and voice

he would create living dimensions from maps and charts,

call forth stories from tilted cliffs and tumbled boulders,

revealing within the flow of geologic time

the tide of the living skin of the living Earth.

The rocks called to him,

whispered their secrets to his soul,

and he gave voice to their songs.

Their spirit flowed in his veins,

as his now flows in theirs.

The rocks, they called to him.

- Robert Ramming 11/18/18

I was fortunate to be a graduate student at UC Davis while Eldridge was a professor there. His class on tectonics, and remarks in seminars, in hallways and at outcrops all encouraged lively thought and discussion, and gave me the impression that my participation was important. I think many people shared that reaction and got the impression that we might be on to something new and unexpected.

I was fortunate to be a graduate student at UC Davis while Eldridge was a professor there. His class on tectonics, and remarks in seminars, in hallways and at outcrops all encouraged lively thought and discussion, and gave me the impression that my participation was important. I think many people shared that reaction and got the impression that we might be on to something new and unexpected.

Years later, while working as a professor at a university in Japan (speaking of unexpected!), I was able to bring three undergraduate students to Davis and the Sierra Nevada foothills for fieldwork for their research projects. The timing worked out so that we were able to join Eldridge leading a field trip--the attached photo gives an accurate impression about how much fun it was.

with great regard for Eldridge, and with condolences to his family, friends and colleagues,

Tim Fagan (UCD, 1997)

Dept. Earth Sciences

Waseda University

Needless to say, I was shocked when I received a call about Eldridge's untimely death. Eldridge was a remarkable guy who impacted so many of us. I had him in several tectonics seminars at Davis (couldn't resist them; one of the reasons I took so damned long to get out of there). He was also on my orals committee and the advisor to my ancillary dissertation proposal on the paleomagnetic constraints placed on the rotation history of the Troodos Ophiolite. I spent many, many hours with him in his jeep driving to and from field trips. It was always an enlightening experience. Two things come to mind. One, he described his groundbreaking work on the development of plate tectonics, particularly the role of ophiolite studies, as something anything could have done; that is, the "moment made the person" not the other way around. He went on to say that any graduate student who had been working on similar problems in the '60s would have accomplished the same thing. Pretty humble for a star at his zenith, no? Second, as we were bouncing along on a dirt road in the northern CA Coast Ranges somewhere near Yolla Bolly Mountain, I told him that I was thinking of accepting a job at CSU Bakersfield (at the time, CSU College) and would treat it as a stepping stone to a university with a great department. His response was "or, you could make THAT one a great department."

Between Eldridge and Bennie Troxel, I lost a couple of key mentors this past year or so and recently, a dear friend from grad school in Ray Beiersdorfer. Getting on in life, I guess. All of you stay healthy.

Rob Negrini, Ph.D. '86

Professor Emeritus

Geological Studies

California State University

Thoughts on EM2

When I first met Eldridge after arriving at UC Davis in 1990 he welcomed me warmly, proposed some projects in the northern Sierra, and told me some mildly off-color stories using some fairly colorful language. I immediately thought he was my kind of guy. I had brought with me another idea, in particular I described to Eldridge the skeleton of a regional tectonics project in western Argentina, something out of the realm of any UC Davis geology department experience. Instead of rolling his eyes and throwing up obstacles he associated the idea with his recent trip to Antarctica where he’d met Victor Ramos from the U. of Buenos Aires, as well as developed his nascent SWEAT hypothesis. Eldridge immediately wrote Victor a letter and also put me into contact with the research group at Cornell. Then he stood back and patiently let me get the project rolling, helping when I asked, but really letting me develop it over the course of 3 years rather than directing it. I can’t tell you how much I appreciated his support and the freedom to pursue a rather nebulous and slow developing graduate research project.

Over the course of the 7 years I was at UC Davis, working toward my doctorate, I experienced Eldridge’s many aspects. I grew to appreciate his seemingly wild ideas as intuitive leaps forward resulting in conceptual advances that, while often slightly wrong in detail, strongly impacted the direction of the tectonics community. I grew to understand Eldridge’s commitment to geosciences was greater than simply the commitment to do good research, but the desire to serve and to better the geosciences – something that rubbed off on me. I also saw Eldridge’s human side – whether it was closing the door between his office and his ‘lab’ (where I sat) lining up 3 chairs side by side, then laying down to take a nap after lunch, or proudly telling me about what his children were doing. And there was the very urbane and civilized side exemplified by how he ate lunch in the field in Argentina – he would pull out his pocket knife, carefully cut his apple into quarters, remove the core, and eat it deliberately… only to follow by laying back, pulling his hat over his eyes, and taking his post prandial rest.

Though Eldridge did not participate directly in the Argentina research project he never failed to support me with patience and trust. Throughout the ups and downs of the seven year project Eldridge treated me as an adult and I felt like a peer from the beginning, something I valued deeply and will always remember as a model for how I should live my geoscience life.

Steve Davis, PhD 1997

A Thank You for Eldridge.

It is impossible for me to adequately convey what Eldridge meant to me. No person outside of my parents had a bigger positive influence on the course of my life. To me he was my sensei, Jedi Master, and second father all rolled into one. Over the years I have had the good fortune to meet and get to know pretty much all of the major figures in geology that I had read about and admired as a student and I can say without reservation nobody could have connected with me as an advisor and raised my scholarship the way Eldridge did.

I can't help thinking how fortunate I was to sort of sleep walk into being Eldridge's grad student. I chose Davis because of geographical convenience and Eldridge as potential advisor because my tectonics professor at UC Berkeley, Walter Alvarez, had mentioned him as one of the heroes of the Plate Tectonic Revolution. As a perfectly foolish student I never bothered to contact Eldridge before I applied, nor did I see him after acceptance into the program (contrary to what I advise my own students to do now), until I visited Davis about two weeks before my first term started to look for an apartment. In that first meeting, I had the audacity to tell him what I planned to do for research and he, after seeing I had already begun serious geologic mapping of the Franciscan Complex ("OK, so you have a map"), encouraged me to follow that path. However independent I was, it was Eldridge's mentoring that transformed me from a raw enthusiastic student into a scientist. He never directed me to do this or that. Nor did he come after me nor schedule appointments to check on my progress. Instead, he mentored in a variety of ways. First was by example: to listen to him talk about research and various subjects showed me how to hunt for and identify problems of major scientific interest and impact. Of course, his epic record of publication of "home runs" was itself an illustration of this. Think Big. Aim High. His thinking as a scientist also came out in interaction with him through debate and discussion of ideas and hypotheses. We would have these vigorous debates that I'd call "tectonic shoot outs" in his office. I remember about a half year after I graduated, I visited him, and we sort of spontaneously ended up in a spirited hour plus long debate about some Cordilleran tectonic problem. After it was over, Eldridge said "Wow, I really miss that. We need to make sure we do that more often." His Think Big philosophy was also conveyed through his comments on our thesis proposal drafts and drafts of our manuscripts. His signature comment that we'd see so often was "So What?" And then I remember the way he would stimulate us to think in his graduate classes. He would say things that would get our minds so abuzz we couldn't simply walk out of his class and go back to our grad offices. Rather we would continue to discuss various aspects of tectonics for a long time while looking at geologic maps. I think of that magic and wish I could pass the same on to my own classes, but alas, there was only one Eldridge.

Eldridge was a role model far beyond being a great scholar, though. I remember how family oriented he was and how he did not camp out in his office or lab in the way that was considered the norm in many institutions; he left his office each evening in time to go home for dinner with his family. That balance in life and work was something that I figured I would want to follow if I ever became an academic.

As the years went on he continued to be a mentor, friend, and father figure to me. His formal reviews of some of my papers were mind blowing. His reviews were always shorter than those of the other reviewers but he would always pose the most difficult questions, commonly questions I felt I could not adequately answer. He could see the big picture and the big scientific issues more clearly than anyone I have known. It was always such a pleasure and a terrific learning experience to go into the field with him, too. I believe my first field trip with him (1985?) was a graduate class field trip to the Feather River area and that eventually led to my research interests in that area, and also tagging along on his last field trip. Much more recently (2015), he persuaded me to accompany him to look at the geology in the Wilbur Springs to Lake Berryessa as a part of acquiring background information he wanted to help lobby for the creation of what became the Berryessa-Snow Mountain National Monument. That was a particularly special trip for me because I think that was the only time it was just him and me, and it was really neat to be able to "discover" some things while he was along with me. I felt like a boy showing off to his dad.

It is difficult for me to accept his passing, but as much as I miss him, I can't help think how lucky I was to have met him 35 years ago and how amazing those years were. I will continue to strive to be worthy of his teaching.

Thank You, Eldridge. I will always be in your debt.

John Wakabayashi

Professor of Geology, California State University, Fresno

I didn't know Eldridge for very long, but I did have the good fortune of attending the Greece trip with him this past September. As a geochemist, I thought my chances of being accepted as a participant on this trip were pretty slim, given that it was a structural geology/tectonics trip. I am convinced it was Eldridge who accepted my application as he was so passionate about sharing his love of tectonics with people from other fields of science. It is because of Eldridge's passion that I was able to see the Pindos and Vourinos ophiolite with him. The trip to Greece rekindled my love of structural geology and tectonics, and I am so grateful to Eldridge for facilitating the trip. But more importantly, it was also a blessing and a treat to get to know Eldridge on this trip. Eldridge was one of the kindest and most humble people that I've ever met. Even when I asked a seemingly dumb question Eldridge would respond in such a way that would help me understand without making me feel stupid.

Elizabeth Grant

PhD Student - Igneous Petrology, Geochemistry

Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

University of California, Davis

If it hadn’t been for the mentoring I received from Eldridge Moores, I would not have followed the path of my career. In the early 1980s, I was a UC Davis undergrad majoring in something else, but didn’t have the passion for it that I did for geology: I thought I was just dabbling in geology by enrolling in a few classes for fun and to fill out my schedule. After taking a more advanced course from Eldridge and doing very well, we had a serious conversation. In those days, I was seriously disabled, and got around campus in a wheelchair: the thought of a “handicapped kid” going into geology seemed ludicrous. But Eldridge encouraged me to pursue the subject more deeply, indicating that the geoscience world ought to look beyond my physical impediments to my mental abilities, and he’d see to it if necessary with personal recommendations.

When UC Davis later started an interdisciplinary Earth Science and Resources graduate program (which eventually became the Hydrologic Science Graduate Group), Moores prodded me to apply, wisely musing that the emergence of earth systems science could transform the geosciences much as plate tectonics did, and pointing out that my background in other fields along with geology would not have been wasted time but an asset. Eldridge was there to give me sage advice over the decades, and I looked forward to seeing him most every autumn at GSA or AGU meetings.

One week back about 1990 it was announced that Eldridge would give the regular Geology Department Friday brownbag seminar, but the title/topic was strangely TBA and seemed to be a tightly guarded secret. My friends and I expected him to reveal some new insight into ophiolites or plate tectonics. Instead, Eldridge came out with his cello and played a 45 minute solo recital! I'd never seen him so obviously nervous and literally sweating copiously- but never did I see him so proud at an accomplishment. Another Friday he announced he would bring in a friend to discuss his latest work. It turned out to be John McPhee, who gave a reading from a draft version of his travels with Eldridge in what wound up as "Assembling California." I remember us being fairly tough crowd and we gave McPhee a lot of constructive criticism, which certainly made the book better.

Eldridge once told me that he was on a trip somewhere, and when the plane touched ground it was the roughest landing he had ever experienced; he had decided to complain to the pilot on the way out of the aircraft- until he looked out the window and saw things moving and the airport terminal physically shaking and dislodging some bits. He had landed at the exact moment of a major earthquake! I like to think it was the Earth itself trembling at renewed contact with a man who unlocked the secrets of its depths.

Tom Gill

Professor of Geological Sciences, University of Texas- El Paso

I grieve for the untimely and tragic loss of my dear friend and colleague Eldridge Moores, an esteemed colleague who will continue to be part of my memories. My heartfelt sympathy goes out to his wife, Judy, and their family.

We have had the good fortune to know each other for almost 60 years, from our days as graduate students at Princeton, to my initiation as a faculty member in the nascent Geology Department, and ending in an enduring friendship as retired colleagues. We were fortunate to be geology students at the beginning of the modern plate tectonics revolution and to have experienced its maturation as a paradigm that helps explain global geology in a coherent context that links geological observations to a theoretical understanding of the underlying driving forces. Eldridge has been a leader in that transition. During that time, he has been an intellectual library rich in knowledge and understanding.

Eldridge has played a critical role in developing the current Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. From the outset he led in the pursuit of faculty with the highest standards, and balanced this goal with an emphasis on diversity and scientific breadth. Much of the success that UC Davis Earth and Planetary Sciences enjoys today is the result of his enduring stewardship.

His major scientific contributions have set the stage for the application of plate tectonic theory to an understanding of global geology and how to think of Earth as a unified system; a research pattern that is much enriched by including an historical perspective of the evolution of the plate tectonic paradigm.

The full scope of Eldridge’s achievements is difficult to summarize. His research record and dedication to UCD attests to his scientific contributions. He has also lived as a citizen dedicated to linking his field of science to societal concerns by serving as Presidentof the Geological Society of America (GSA) and the International Union of Geosciences (IUGG). Both have been beneficiaries of his leadership. In addition, he has collaborated with the Board on Admissions and Relations with Schools (BOARS, of the California Universities Senate) on how to improve science standards so that they align more closely to modern ideas of science instruction. His efforts include his contributions to the discussion between the economic and environmental consequences of industrial hydrofracking and the engineering foundation for reconstruction of the Oroville Dam spillways. In this area of public education about geology his field trips which have traversed northern California from the Sierras to the sea have helped our broader community share an understanding of the geological assembly of California. Along with Judy, Eldridge worked as a member of Tulyome, an organization dedicated to preserving our regional environment – a task critical to the health and wellbeing of our lives and community. All these tangential journeys illustrate the breadth of his contributions.

On a personal level, I will miss the joy of friendship that arises from shared interests and the joint love of music while we participated in university concerts – Eldridge as a cellist in the UCD orchestra and I as member of the UCD chorus.

Ian MacGregor

Memories

Eldridge was truly a great person and a fine geologist. He was a humble and very much down to earth, he never let his great accomplishments affect his outlook on life. My favorite story of Eldridge occurred in 1994 at the 50th Anniversary dinner of Northern California Geological Society that was held at restaurant in Concord. As I arrived that evening in the parking lot of the restaurant, I heard this old jalopy obviously in great distress arriving at the same time. Out of the car appeared Eldridge and Judith who were our guests of honor for that evening. It was clear that the vehicle needed some immediate attention and Eldridge and Judith would have to spend the night inorder to get the vehicle repaired for their return trip to Davis. The assembled people at the dinner offered all kinds of suggestions for night accommodation. Some offered to accommodate them up for the night. He thanked every one but said that he had to rent a car to get back to Davis for an important! engagement scheduled for the following morning. One of the members, realizing the importance of the meeting offered to loan Eldridge his spare car for the return journey. Eldridge accepted. At dinner, I asked Eldridge what was the important meeting he had to attend next morning? He told me that he had a scheduled talk to an elementary class of students. I was not surprised since he truly was a person who gave equal importance to introducing young students to geology. This action was typical of Eldridge, no matter how involved he was in his research and his profession, he always had time for the the ordinary things in life. I saw this on so many occasions,. For example, at GSA meetings I would see him surrounded by students and taking the time to answer their questions and give advice.

The only time I saw Eldridge upset was when on tour as a distinguished lecturer, he arrived to give his presentation without his carousel of slides. Someone had stolen his brief case at the airport. It was hilarious to watch Eldridge tell the story and then use an overhead of quickly sketched figures to illustrate his lecture. Eldridge had one failing, he was not a great artist.

Eldridge was be greatly missed by the geological community and others whose lives he touched. My condolences to his family and the Davis community.

Raymond Sullivan

Professor Emeritus of Geology

San Francisco Stae University

This memory of Eldridge is particularly intended for his wife, Judy, and although it is one that is all too brief, I will cherish it along with all the others that I have of him. The last moments I shared with Eldridge were on October 16, just before the start of the Department's quarterly, noon-time, graduate seminar on Structure and Tectonics led by Sarah Roeske. As is usually the case, I was early and waiting in the open area outside the Moores conference room for its door to be unlocked and the room opened when Eldridge appeared. His hands and arms were loaded with what he was carrying, including his lunch, and while fumbling for his keys, he greeted me with a smile and "Hello Doug, I guess this is the right room." I returned his "Hello" and added "Well, the name is right." That got his quick chuckle. We then took our seats at the conference table and I welcomed him home from his recent travel. I meant from Greece, but he thought I was referring to his trip to Atlanta from which he and Judy had recently returned. He then told me that he had turned 80 shortly after that. I wished him "Happy Birthday," told him he didn’t look a day over 65, to which he replied “Yeah, right,” and, as he began eating his sandwich, he told me that when he made his own sandwiches they were quite plain and simple and that the sandwiches Judy made for him were always much richer and healthier for what they contained. I could see by the slice of tomato that this sandwich was more involved and said that it must be a "Judy sandwich" to which he nodded his agreement.

Judy, while so many others have and will recall their more momentous memories of Eldridge and his numerous achievements, I want you to know that, by this seemingly simple comment of his, you were always on his mind.

Now, Eldridge belongs to the ages; a fitting tribute for one who had such a profound appreciation and understanding for the meaning of time.

With great respect for you, your family, and Eldridge, I wish you the very best for now and all the days to come.

Sincerely,

Doug Sheeks

M.Sc., Geology

UC Davis, 2016

Portraying Eldridge

I had the good fortune of working with Eldridge for my Masters degree at Davis during the early 2000’s. Two of my favorite memories, of many, center around the times I portrayed Eldridge. Before arriving in Davis, most of what I knew about Eldridge was based on reading Assembling California by John McPhee. I knew I was going to be working with a legend, and deep down I was a little intimidated. However, one of the things that I grew to appreciate about Eldridge was that despite all of his accomplishments and accolades, he did not take himself too seriously. This was made clear to me after I attended a graduate student-hosted Halloween party dressed up as Eldridge. I grew my beard out and trimmed it into the Eldridge’s signature style, sprayed my beard and grey/white, found some appropriate glasses and fashioned a bolo tie. My decision to dress as Eldridge stemmed from the fact that he was a living icon in the geologic community and because the costume would be appreciated by the geology crowd at the party. However, when I left the party I became apprehensive about what Eldridge would think about my costume choice should he hear about it. Would he be offended? Would he think I was mocking him? Would he take it as a sign of disrespect?

The next work day I stopped by Eldridge’s office and summoned the courage to tell him, and show him photographic evidence that I went to the Halloween party dressed as him. I explained why I chose to go as him and tried to back it up with the classic line, “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery”. After what seemed like an eternity (probably 2 seconds), a glint appeared in his eyes, and he began laughing. He was genuinely amused, and I think flattered, that I would have the nerve to attend a party dressed as him. It was clear that he did not think that what I did was an insult- he saw the humor in it, and took it for what it was, much to my relief.

That same year, Eldridge had announced that he was going to be retiring. For the annual winter party, two months after I dressed as Eldridge for Halloween, I co-wrote a skit about the potential department search to replace Eldridge’s position, with the idea that I would reprise my “role” as Eldridge. My Halloween stunt had gone around the faculty like wildfire, so there was a lot of speculation about whether or not I would reprise the role. I showed up to the party dressed as myself (without any beard trim or hair coloring), and Eldridge came up to me with a glint in his eyes and saying “I see you’re not me”. I just told him “not yet” and he smiled. After dinner, I got into “character” in a side room and then came out to perform to considerable laughter from the faculty, particularly Eldridge. The best part came afterward however, as Eldridge came up to me and offered his “notes” on my performance of him.

That same year, Eldridge had announced that he was going to be retiring. For the annual winter party, two months after I dressed as Eldridge for Halloween, I co-wrote a skit about the potential department search to replace Eldridge’s position, with the idea that I would reprise my “role” as Eldridge. My Halloween stunt had gone around the faculty like wildfire, so there was a lot of speculation about whether or not I would reprise the role. I showed up to the party dressed as myself (without any beard trim or hair coloring), and Eldridge came up to me with a glint in his eyes and saying “I see you’re not me”. I just told him “not yet” and he smiled. After dinner, I got into “character” in a side room and then came out to perform to considerable laughter from the faculty, particularly Eldridge. The best part came afterward however, as Eldridge came up to me and offered his “notes” on my performance of him.

A tangible outcome of me dressing as Eldridge was that it enhanced our working relationship- our interactions were less rigid, more relaxed, and typically involved laughing over something ridiculous. From that point onward, I felt like I got to know Eldridge beyond the formal advisor-student relationship, and what I saw was that in addition to being a pre-eminent scientist and science communicator, he was a humble, generous, and incredibly thoughtful man. I am the better for knowing him, and am grateful for the time I spent with him.

A tangible outcome of me dressing as Eldridge was that it enhanced our working relationship- our interactions were less rigid, more relaxed, and typically involved laughing over something ridiculous. From that point onward, I felt like I got to know Eldridge beyond the formal advisor-student relationship, and what I saw was that in addition to being a pre-eminent scientist and science communicator, he was a humble, generous, and incredibly thoughtful man. I am the better for knowing him, and am grateful for the time I spent with him.

Eric L. Brown, PhD

Assistant Professor

Department of Geoscience

Aarhus University

Eldridge was a valued and loved colleague. I never studied or worked with him, but he was still a presence. I got to know him through his service to the Geological Society of America. He always had time to chat, and we covered all kinds of topics. I loved his sense of humor and ever-present smile. He was a man who struck me as one who loved and embraced life and all its trials and opportunities. I will miss him.

Judy Parrish

Past President, GSA

Professor Emerita

University of Idaho

Eldridge was with us here in Greece just a month before his passing.

Eldridge was with us here in Greece just a month before his passing.

That time was a blessing where he was again in his mountain of Vourinos, and excited as ever by what can be learned there (which we are still learning). This gave us time to let him know how loved he was by us and by the folks of the region. They honored him by dedicating a rather large mantle boulder to him, along with a marble plaque. At this ceremony, there were present representatives of all the mining and quarrying concerns in the region, essentially recognizing that without the advances in basic research he initiated, they would not be in business today. A chrome mining museum in the village of Chromion is being established, and will probably bear his name.

I can't over-estimate how he has entered the local legends of our villagers. Some worked for him as field assistants, others think he was the one who bought them an ice cream when they were kids. He was definitely adopted by the village back in the 60's. The visitors of the last field trip have been adopted as well.

Here is the personal eulogy I've written to be published within the Greek Geological Society

Annie Ewing Rassios PhD (1981)

From the first time I met Eldridge as a doe-eyed first year PhD student, the things that struck me about him was his presence in the room. As is probably true for many of us, I learned his name and his reputation from textbooks and from Assembling California, and I knew he was a titan in the world of tectonics. Given this and my experiences with other big name figures, I figured he would be an unavoidable character. And he was — but in a completely different dimension than I expected.

Our first run-in was during a meeting of the structure/tectonics lunch seminar one of my first weeks of class, and I must admit that I didn’t identify him immediately. This wasn’t because he was trying to be unobtrusive. In fact, quite the opposite: everyone in the room was so at ease, and he was discussing everyone’s personal research and interests so easily and naturally, that he was simply and inevitably a part of the conversation. In my eyes, this was truly one of his gifts. One might call it humility, but I don’t think that’s quite right. Instead, it was a genuine interest in research, in the scientific process, and in contributing to the dialogue. I always got the impression that he viewed us graduate students as colleagues from day one, with valuable ideas to contribute and perspectives to provide.

Of course, the way that he put us all at ease had a flip side as well. Every once in a while, he would sneak a comment into the conversation that would almost go unnoticed, until you realized how profound it was.

Eldridge provided grace, generosity, and wit to the department in so many ways, and he meant an incredible amount to all of us. I hope that those of us who he inspired to follow in his footsteps can, together, begin to fill the shoes he leaves behind.

Charles C. Trexler

Visiting Assistant Professor

Department of Geology and Geography

Ohio Wesleyan University

I was so lucky to join Eldridge in September of this year to visit the Vourinos Ophiolite and surroundings in the Macedonia region of northern Greece. He was a wonderful guide, sharing what he knew, welcoming us all to explore and learn about this place that had played a pivotal role in his life and our understanding of plate tectonics.

I was so lucky to join Eldridge in September of this year to visit the Vourinos Ophiolite and surroundings in the Macedonia region of northern Greece. He was a wonderful guide, sharing what he knew, welcoming us all to explore and learn about this place that had played a pivotal role in his life and our understanding of plate tectonics.

I had spoken with with him about ophiolites and how they get incorporated into continents on many occasions (which inspired the idea I proposed in my NSF Career grant when I was an assistant professor) but visiting these places with Eldridge felt like reliving the history of the discovery of plate tectonics.

On the last day of the trip, we returned from dinner in Thessaloniki to the hotel; and Eldridge sat down at the piano in the lobby and played. It was a moment I cherished and will keep in my heart always.

Magali Billen

Professor, UC Davis Earth and Planetary Sciences

During the mid-80’s, I collaborated with Eldridge (and our wonderful students and colleagues) when we revisited his ground-breaking 70’s research on the Troodos Ophiolite. We spent some 5 field seasons there, often getting out in the early mornings before it got too hot, then taking siestas during the heat of the afternoon, and finishing the day with evening sessions at the local cafe, enjoying meze, drinking cold bottles of Keo beers, and talking Geology and politics.

During the mid-80’s, I collaborated with Eldridge (and our wonderful students and colleagues) when we revisited his ground-breaking 70’s research on the Troodos Ophiolite. We spent some 5 field seasons there, often getting out in the early mornings before it got too hot, then taking siestas during the heat of the afternoon, and finishing the day with evening sessions at the local cafe, enjoying meze, drinking cold bottles of Keo beers, and talking Geology and politics.

One of the many memorable experiences was the day a poisonous (?) snake was discovered in the yard of our rental house. Eldridge dispatched the snake and displayed it for all of us.

He was a hero in so many ways.

Peter Schiffman

Professor Emeritus, UC Davis Earth and Planetary Sciences

I am so saddened to hear of the sudden passing away of geology legend Eldridge Moores. I worked as a post-doc in the department from 2011 through 2016. I didn't know Eldridge very well, but do have a fond memory to share. Eldridge often attended afternoon seminars. On occasion, he would appear to be asleep during the lecture, but regardless, during the question/answer session after talks, he would still ask a profound question that often sparked a great conversation. Other grad students/post-docs and I would often comment after the talks and ask... "How does he do that?" It was pretty amazing!

He left his mark on the UCD Geology (Earth and Planetary Science) community and will be missed by all.

Thinking of all of you,

Jenn Fehrenbacher

I have many good memories of geology discussions with Eldridge, from my very first GSA meeting, to a good visit in Bellingham in the late 80s or early 90s, to many other GSA gatherings.

My condolences to his family, and to his UCD family as well.

One of my more recent memories of Eldridge is how surprised and pleased my spring, 2017 California Geology students were when I showed them news footage of Eldridge hammering on weathered greenstone in the Oroville dam's back-up spillway, and talking about fresh vs. weathered rock. They'd been reading about Eldridge in "Assembling California", but didn't expect him to appear in the "update the textbook / today's news" part of the class. He spoke to such a tremendous range of folks!

Dr. Susan Cashman

Dept. of Geology

Humboldt State University

3 memories:

1) Eldridge would be lecturing. He’d stop. Look around. And then say to the class “Clear as mud”. Not a question but a statement. And everyone in the room agreed.

2) I took Structural Geology in the Fall Qtr 1976. We took many field trips on weekends during the course. Once we got to a location, everyone would pile out of the Suburbans, and follow Eldridge to an outcrop where he would just start lecturing before everyone got there. Then he would finish and while students were taking notes on what he said, Eldridge would rush off to the next outcrop and start lecturing before anyone else showed up to listen. Maybe 1 or 2 students would get there before he finished and then he’d be off to the next spot and begin his lecture. Nobody could keep up with him including the TA’s. So when it came to write the field reports, nobody, including the TA’s, had any idea of what they were supposed to be writing about. The subsequent grades on the reports reflected what the students got out of the field trips.

3) Even so, I took all of Eldridge’s courses on Plate Tectonics, enjoyed all of them, and went to grad school at Berkeley hoping to work with Walter Alvarez looking to continue research in that area. But life had other plans for me.

Ted Asch, Ph.D., P.Gp.

Graduated in 1978 from the Geology Dept.

It is very difficult to believe that Eldridge is gone. He was a wonderful person; a friend, mentor, teacher, colleague, research scientist. There are a great many fine teachers and scientists out there, but I have never known anyone as beloved and respected as Eldridge.

He was a key figure to me, as one who introduced, taught, mentored and encouraged me in the field of geology. Many others can say the same.

Recently I have been very fortunate to be able to reestablish contact with Eldridge and to join him, his students, fellow colleagues and alumni on a visit to some extremely important field study sites in Greece – places we can normally only read about. Through his continued research over the years, Eldridge has introduced and expanded upon the value of that work, bringing forward our fundamental understanding of Earth processes. His large volume of work will live on, of that I am certain.

Thanks very much, and Bon Voyage, Professor!

Rich Drumheller

Geologist

B.S. Geology 1969-73

Although I’m not affiliated with UCD, I have a undergraduate degree in geology and I’ve known Eldridge for many years in various capacities, mostly associated with Putah Creek. After retiring from a long career in endangered species conservation, I once again had more time to explore my other passion of field geology.

I longed to create a geology road guide to the Putah Creek watershed, similar to geology conference field guides, with milepost markers and descriptions, but written in less technical terms. Like Eldridge, I hoped to engage, educate, and inspire non-geologists about the geological landscapes around them. While gathering existing geological papers and maps for the area a couple of years ago, I found mismatching adjacent geology maps, showing lithology conflicts at the mouth of Putah Creek Canyon.

I asked Eldridge if he knew someone who could help me make sense of the map conflicts. I was astonished to hear him offer to go with me, one on one, out to the field, because I was convinced that he had so many other things on his schedule. But he was quite eager to go, and right away. It really showed his generosity, his passion and curiosity for local geology, and his willingness to share his knowledge and time with others, no matter what their affiliations or stature in the field.

We met up with Dash Weidhofer, manager of California Audubon’s Bobcat Ranch, at the ranch HQ, to explore the area of map conflict. The ranch is almost 7,000 acres in size, covering the entire north side of Putah Creek Canyon. In a geological sense, it offers access to Pliocene volcanic tuffs, extensive outcrops of Miocene Lovejoy Basalt, salt springs, and a continuous sequence of much of the Great Valley Sequence, from the youngest beds to very old ones. It would make a great geological field laboratory for UCD students.

At the top of Rattlesnake Rock ridge, Eldridge looked at the steeply dipping Tehama Formation beds and the massive columnar Lovejoy Basalt that was tilted almost horizontal. Below us to the east of us were starkly contrasting, almost-horizontal Tehama beds. Some structure clearly laid between the two areas. He turned to me and said “I think you’ve found something very interesting here”. Wow, what an honor to hear that from so distinguished a geologist! He perceived that we might have found a surface expression of the fault that set off the 1892 Winters earthquake.

Eldridge proceeded to make time to join me several times in the field at Bobcat Ranch, poking up various canyons to more precisely locate the fault, if it indeed existed. At one point, as Dash and I hiked up a very steep grassy hill, I told Dash to wait up. After all, we had a fellow who was almost 80 years old with us, so we shouldn’t go too fast. I turned around to see how Eldridge was doing, expecting to see him far down the slope. Wrong. He was right behind us young bucks (ok, at 60, I wasn’t so young, but compared to Eldridge…).

We never found a clear fault break on the ranch, due to poor exposures, but we were able to narrow the zone down to a few hundred meters. In looking for the fault, I ended up mapping the geology of Bobcat Ranch, which finally resolved the mapping conflict that initially drove me out there.

Eldridge and I, along with Peter Schiffman, Judy, and Bob Schneider also started to work more seriously on my even bigger initial idea of a road guide for the Putah Creek watershed. As of this summer, before wildfires and other things got us somewhat derailed, we had created a very rich first draft of the guide, including not just geology, but also ecology and cultural history mileposts. We’ll have to find a way to finish it. It would be a great testament for his passion at educating and inspiring wonder in others, not just college students and professions but the general public as well, about geology.

He was a true geology hero.

Marc Hoshovsky

Sierra Excursion with Eldridge

My BMW in the background dates it somewhere around 2002,

at the early days of the Iraq War when I bought it the year before.

Eldridge reveled in our pristine surroundings, ingrained in his

very being, on a summer weekend with wives at a North Yuba

cabin midway up to the ridge of his beloved Sierra Nevada,

where I showed him how to catch a fish from a midriver rock.

As a frantic trout fought to survive my fake fly hooked

hard in its mouth, I handed Eldridge my flyrod, taught him

to keep tension hard on the line, to control the fish jerking,

prevent its potential downstream run, to hold tight till

it tired, pull it up to our sides. I slid it into my hand-held

net, brought it up to shore, hit its head hard with a stone,

then sliced out its guts. Together, we presented our fish

to our wives for our first evening meal of the trip.

Next morning we set out to climb a mountain, Eldridge’s

forte, five miles by car to a parking lot, a half-mile hike up

a dirt road to its end, then the final ascent to a fire lookout

at eight thousand six hundred feet, the top of Sierra Butte.

Hiking up the road was a breeze for Eldridge and Judy, whom

Ann and I found resting in shade near the final ascent. Assuming

they’d completed the climb, I advanced to the base of a firm metal

ladder, the only way to the lookout station, a vast panorama ahead.

Looking up to the top, I saw two chasms to cross, each bridged

by a ladder with rungs a foot and one half apart, two hundred to get

to the top. After three hesitant steps, a vast chasm unfolded,

hundreds of rocky feet down. With heart racing, sweat pouring,

I made an unclimbed retreat to firm ground to rejoin the rest

for the walk down the dirt road. Years later, at one of our church’s

old guys’ meetings, the topic of mountain climbs emerged, specifically

the views from the top. When I related to the group my failed ascent,

Eldridge looked over to me and simply responded:

“I chickened out too.” This was just one the ways we bonded.

Charles H. Halsted MD

Emeritus Professor of Internal Medicine (retired), School of Medicine, UC Davis